Noor Jahan ka Junta: The Power Circle That Quietly Ruled Jahangir’s Court

MEDIEVAL INDIAN HISTORYWOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY

S. K. Sinha

11/13/20255 min read

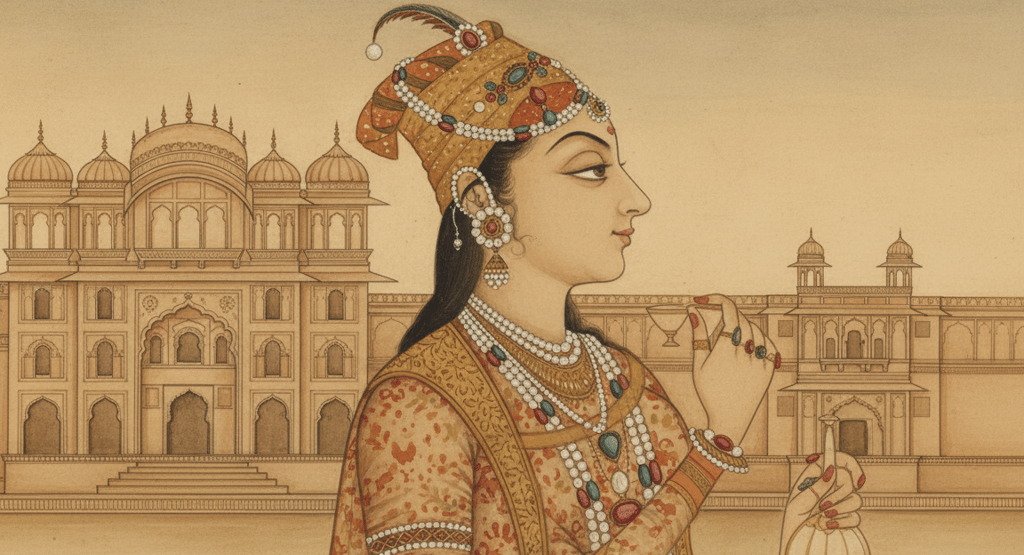

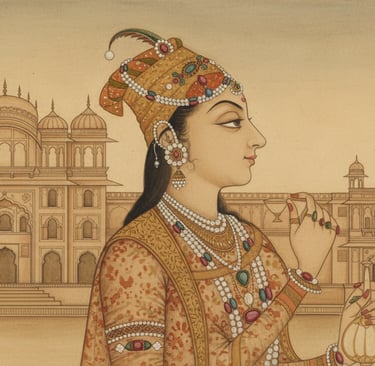

In the twilight years of Emperor Jahangir’s reign, when the empire shimmered with Persian aesthetics and Mughal grandeur, a soft sway of pearls at a woman’s temple told a story far bigger than jewellery. The ornament was the jhumta, a side-headpiece Noor Jahan made iconic. But behind this delicate shimmer existed something far more potent: a political faction historians later referred to as the “Noor Jahan junta” or “Noor Jahan ka guth”.

It was a circle of power built not through armies, but through intelligence, family alliances, administrative brilliance, and the emperor’s trust. This network reshaped Mughal politics so deeply that its echo can still be traced in paintings, architecture, court reforms, and succession battles.

This is the untold history of that faction: the people who stood behind Noor Jahan, the politics they influenced, and how a queen’s ornament became a metaphor for power.

The Jhumta: Ornament, Identity, and Metaphor

The jhumta Noor Jahan wore was not an ordinary piece of jewellery. It was a gold-and-pearl jhoomar resting gently on the side of her forehead, often captured in Mughal miniatures. Scholars associate her strongly with this ornament because she popularised it so extensively that it became part of her imperial identity.

But in literary and historical usage, especially in Persian-Mughal court culture, ornamental metaphors often referred to political groupings. Just as a cluster of pearls formed a jhumta, a cluster of powerful individuals around Noor Jahan was described metaphorically as her junta, or her “group”.

This layered meaning is why the phrase appears both in cultural and political contexts.

The Rise of Noor Jahan: A Woman at the Centre of Power

Noor Jahan, born Mehr-un-Nissa, entered the Mughal court not as a royal but as a woman of exceptional intelligence and refinement. Her marriage to Jahangir in 1611 changed the equation of power in the empire.

The emperor trusted her judgment; he admired her calm command, her administrative intuition, and her grasp of politics at a time when his own health, compromised by addiction, wavered.

Through this trust, Noor Jahan gained unprecedented influence:

Farmāns were issued in her name,

Coins bore her titles,

She appeared in jharokha darshan alongside the emperor, an honour never granted to any Mughal woman before her.

But Noor Jahan did not operate alone. She built a power network, carefully woven through kinship and loyalty, a network that later chroniclers described as the Noor Jahan faction.

Primary sources such as the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri (Jahangir’s memoirs) document her involvement in governance, while historians like Ellison Banks Findly in Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India detail how she became the only Mughal woman to issue farmāns and appear on coins.

The Core of the Faction: The People Who Empowered the Empress

Mirza Ghiyas Beg (Itimad-ud-Daula)

Noor Jahan’s father, Mirza Ghiyas Beg, rose from a struggling Persian migrant to one of Jahangir’s most trusted officials. His sharp administrative mind and unwavering loyalty made him the backbone of Noor Jahan’s political circle. With Jahangir’s support, he became the empire’s Wazir, a position of enormous influence.

Historian John F. Richards, in The Mughal Empire, notes his crucial role in shaping Mughal administration.

His tomb in Agra, known today as the Itimad-ud-Daula’s Tomb, remains a symbol of the family’s rise and Mughal-Persian artistic fusion.

Asmat Begum

Although less documented, Asmat Begum, Noor Jahan’s mother, was a respected presence in the domestic and cultural sphere of the court. Her lineage, refinement, and networks within the Persian nobility strengthened the family’s prestige. In a court where domestic alliances were deeply tied to political stability, her presence mattered more than the chronicles explicitly state.

Asaf Khan (Abul Hasan)

Asaf Khan, Noor Jahan’s brother, was arguably the most powerful noble of the empire after the emperor himself. His positions, first as Khan-i-Saman and later as one of Jahangir’s highest ministers, gave him control over resources, mansabs, and court appointments.

He also became the father of Arjumand Banu Begum, better known as Mumtaz Mahal, whose marriage to Prince Khurram forged a link between Noor Jahan’s family and the future emperor Shah Jahan.

Prince Khurram (Later Shah Jahan)

For a time, Prince Khurram aligned with the Noor Jahan faction. He benefitted from Asaf Khan’s backing and from the goodwill Noor Jahan extended to him early in his political career. Although he later rebelled and broke away, his inclusion in the early structure of the group shows how pivotal Noor Jahan’s network was in succession politics.

Ladli Begum

Noor Jahan’s daughter, Ladli Begum, played a subtle but crucial role in the faction’s ambitions. Noor Jahan’s attempt to marry her to Prince Khurram was a strategic move to secure the future of her faction. When Khurram refused, the political fabric began to shift. This rejection triggered tensions that eventually led to Khurram’s rebellion and reshaped Mughal succession.

Why This Faction Emerged: The Politics Behind the Power

Jahangir’s declining health left a vacuum in the centre of imperial decision-making. Noor Jahan stepped in not merely as a consort but as a stateswoman. She needed a strong, dependable circle to maintain administrative continuity and to preserve the empire’s stability.

Her faction served three purposes:

1. Administrative Control

With Jahangir incapacitated at times, the faction took charge of appointments, promotions, revenue, and justice. Their governance style blended Persian administrative finesse with Mughal imperial structure.

2. Succession Strategy

The Mughal throne was never devoid of contenders. Noor Jahan’s group aimed to support a prince who would maintain stability, first Khurram, later Shahryar. In this, the faction resembled a modern political alliance, with marriage, loyalty, and strategy driving its choices.

3. Cultural Diplomacy

This was the golden age of Mughal-Persian aesthetics. Noor Jahan, with her refined taste, influenced architecture, textiles, jewellery (including the famous jhumta), and court etiquette. Her faction amplified these cultural ambitions, leaving a mark visible even today.

The Decline: How the Circle Slowly Unravelled

Every Mughal faction rose and fell with shifting loyalties. Noor Jahan’s group declined when:

Prince Khurram rebelled in 1622,

Asaf Khan gradually drifted away from his sister’s political goals,

Jahangir’s worsening health fractured court alliances,

Noor Jahan backed Shahryar, isolating herself from powerful nobles.

After Jahangir’s death in 1627, Shah Jahan ascended the throne, and Noor Jahan withdrew from political life, living quietly in Lahore until 1645.

But the legacy of her faction, with its ambition, influence, and sophisticated cultural vision, continued shaping Mughal identity long after its political disappearance.

Legacy: The Only Female-Led Political Bloc in Mughal History

The Noor Jahan faction remains significant for three reasons:

It demonstrated that a woman at the centre of a royal court could wield structured, administrative power. Noor Jahan was not merely influential, she was strategically powerful.

It reshaped Mughal culture. From architecture to jewellery, the aesthetics Noor Jahan introduced carried her family’s name.

It challenged gendered narratives about medieval India. Her jhumta was not just an adornment; it was a metaphor for the cluster of power that hung close to her, elegant, steady, and impactful.

History often remembers kings by their conquests, but Noor Jahan is remembered for something rarer, the ability to rule an empire through intellect, influence, and impeccable grace, proving that true power sometimes lies not in the sword, but in the subtle sway of a jhumta/junta.

Also Read: Indus Valley Civilisation: History, Cities, Culture & Legacy Explained

FAQs

Q1: Who were the members of the Noor Jahan faction?

The core members included her father Mirza Ghiyas Beg (Itimad-ud-Daula), her mother Asmat Begum, her brother Asaf Khan, her daughter Ladli Begum, and for a period, Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan).

Q2: What was the significance of Noor Jahan’s junta?

While it was a personal ornament she popularized, the term also became symbolic of her political circle, just like clusters of pearls forming a single ornament.

Q3: Did Noor Jahan really rule the Mughal Empire?

While she wasn’t an official monarch, chroniclers like Jahangir (in Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri) and modern historians confirm she exercised significant administrative authority during his weakening health.

Q4: Why did the faction collapse?

Internal succession conflicts, Prince Khurram’s rebellion, and the death of Jahangir led to the weakening and final dissolution of the Noor Jahan faction.